Cloverfields as of September 2018: Determining the Period to Which it Will be Restored

/North-east view of Cloverfields. / left (“Existing”): Photograph: Pete Albert, 2018. / Right (“Proposed Restoration”): 3D conceptual rendering “cloverfields c. 1784 (north-east),” by Kimmel Studio architects, 2018. note, Rendering is still preliminary and is subject to change.

South-east view of Cloverfields. / Left (“Existing”): Photograph: Pete Albert, 2018. / right (“Proposed Restoration”): 3D conceptual rendering “cloverfields c. 1784 (south-east),” Kimmel Studio architects, 2018. note, Rendering is still preliminary and is subject to change.

Historical Overview

The images above show the before and after of the restoration. To the left you can see a picture of the house as it stands today; to the right, a 3D conceptual rendering showing how the house will look once we restore it to around the year 1784.

For those new to our newsletter and not familiar with the house, Cloverfields is a large brick residence located in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. Built in 1705, it was one of the first brick houses of the region. During the course of the eighteenth century, formal and informal gardens were established around it, and a cemetery was created to the north of the house. In the graveyard we find the burial sites of several members of the Hemsley family, who owned the property during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Many of the character-defining architectural features of this era still survive.

The Cloverfields Preservation Foundation (CPF) currently owns the house and four acres of land surrounding it. In 2017 they engaged a team of experts to restore the house and grounds. The multidisciplinary team comprises specialists in project management, architecture, landscape architecture, history and archaeology. The team consulted with other experts, including specialists in dendrochronology, paint analysis and masonry.

The restoration team spent the first six months of 2018 documenting and investigating the house and the grounds. This research is only the first step of the restoration process. The second step consists of determining the date to which Cloverfields should be restored.

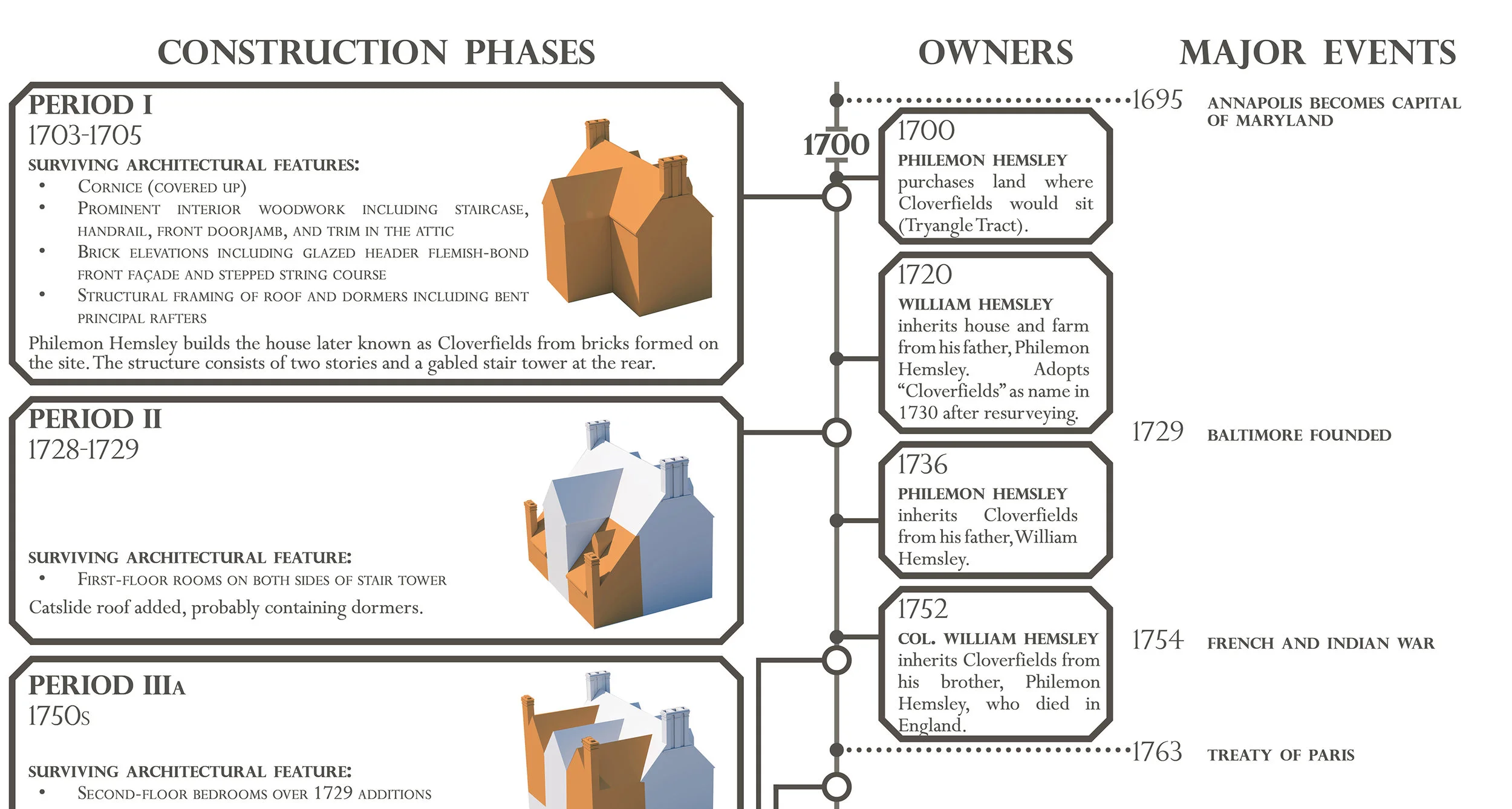

In order to adopt the decision regarding the appropriate period, the team first identified the multiple construction phases the house has undergone. The primary construction periods are shown in the graphics below; you can click through to read about the changes that took place during each one. You can also go through the periods here to see a larger version of the images and the text.

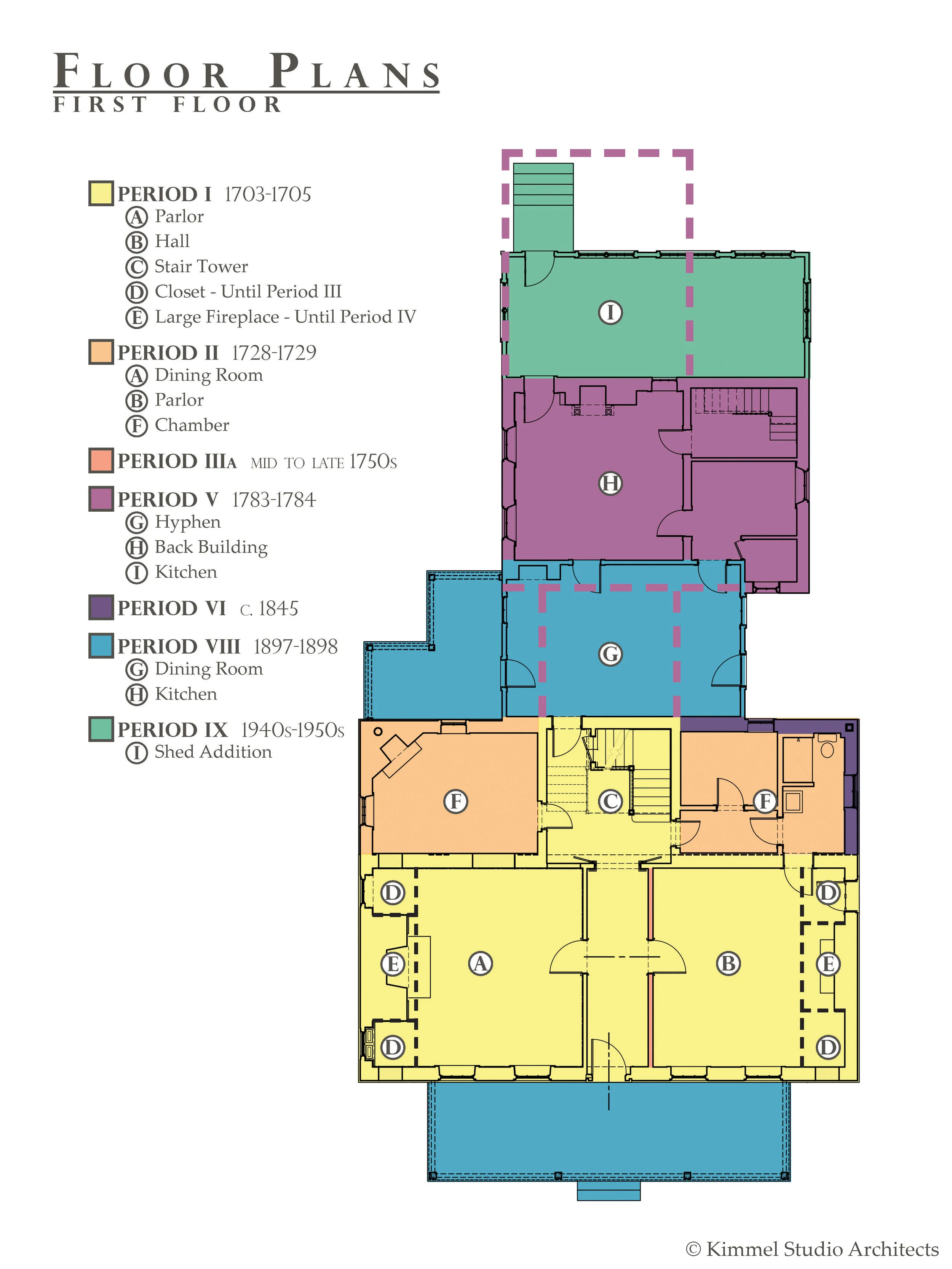

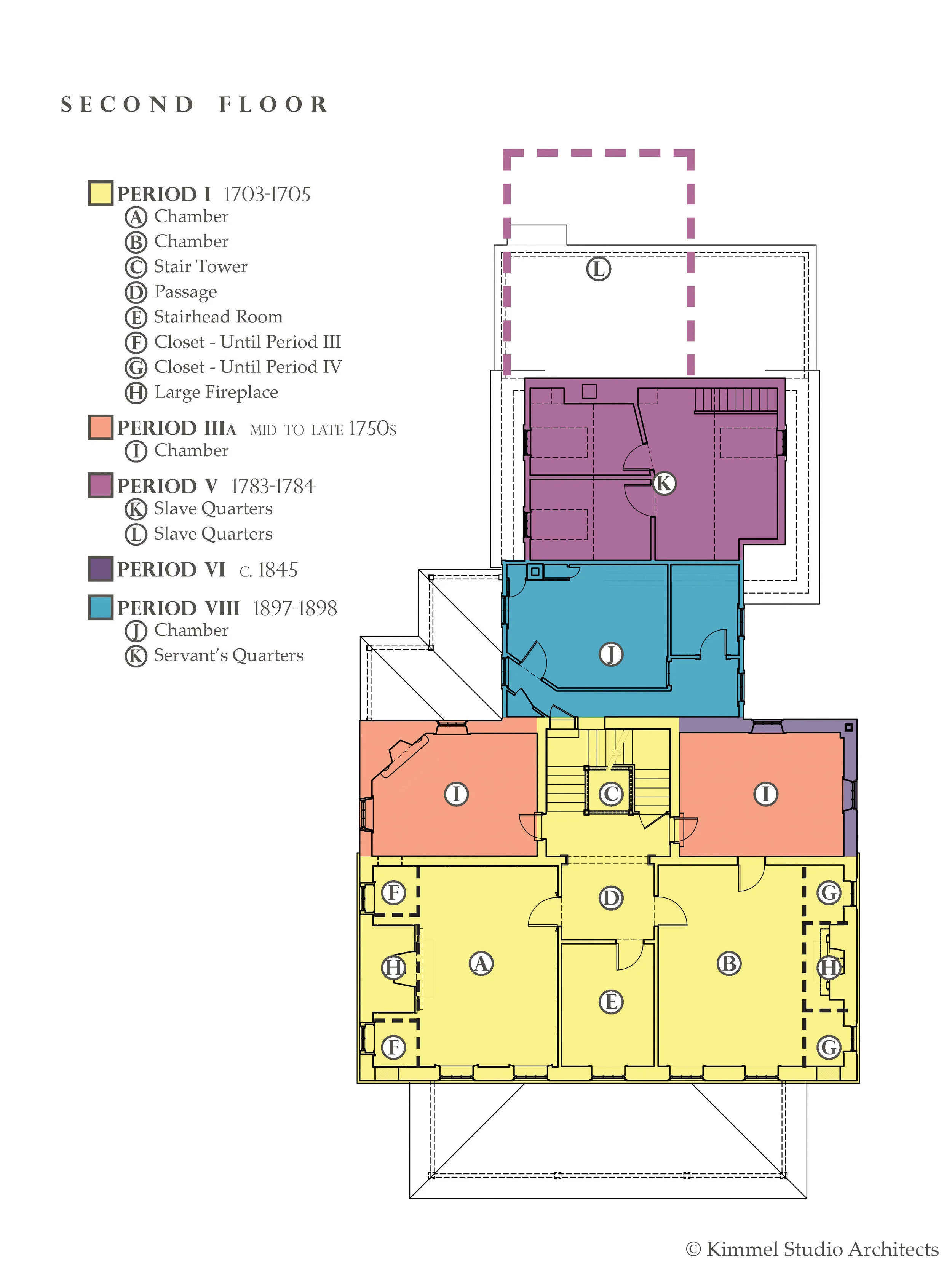

There were rapid changes made in the eighteenth century to enlarge the house. Updates to the house continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ultimately converting Cloverfields from a dignified Eastern Shore mansion to a more utilitarian farm house. The floor plans below illustrate how the rooms and their function changed with the needs of its inhabitants.

Timeline

You can click on the image above to see a graphic timeline showing the modifications made to the house through the years, along with the changes in ownership and major events in US history. It is also available under the History section of the website.

Determining the Period of Most Significance

Upon careful consideration of the findings of its members, the team has determined to restore the house to around the year 1784, and the to restore the grounds to the 1780s. The team feels strongly that this choice preserves the character-defining architectural and landscape features of the site at the height of its use as a power house.

Most prominent among the landscape features are the parterre gardens that likely existed in 1784 but were overgrown by the mid-1800s. Regarding the architectural features, historian Willie Graham tells us:

Construction of the house and all subsequent changes through this date were made to: enhance the fashionability of the site; create rooms appropriate for elite, upper gentry entertainment; establish private quarters for the family; and build a service complex to house enslaved workers and the functions they were required to perform. After that date, the house received few alterations until the 1840s, at which time it was no longer the power house it had once been. By then, Cloverfields had become a commonplace farmhouse not unlike hundreds of others on the Shore at this time.

The 1784 choice, instead, prioritizes the rich history of the decades preceding this year. In 1784 the owner of the house was William Hemsley (c. 1736-1812). He inherited it in 1752, and owned it until his death in 1812. During the decades in which he owned Cloverfields the house was enlarged to its greatest size, the farm was its most productive, and the grounds and gardens most fully developed.

Hemsley was an active participant in many of the major historic events that shaped this momentous era of the history of Maryland and the United States. He was a major in the French and Indian War (1754-63), and a colonel of the Queen Anne’s County militia during the American War of Independence (1775-1783). He then became a member of the Maryland Convention that ratified the United States Constitution in 1788, and represented Maryland in the Continental Congress in 1782 and 1783.

Col. william hemsley - photo courtesy of the new york public library’s digital collections.

But the Foundation will not limit its task to telling his story. As Graham tells us:

A restoration to 1784 could focus beyond recounting Col. Hemsley’s influence, but also more readily portray the life, quarters, and work conditions of his enslaved work force, and allow for a contrasting narrative about the changes in manual labor from the time of his grandfather. Restoration of the service complex could also provide a rich venue for telling the story of manumission efforts of later generations and the effects they had on life at Cloverfields.

In his report “Expansion and Refinement: The Crafting of a Power House” (2018), Graham explains that one of the more historically relevant features to be restored is the extensive service wing Hemsley had built. The wing included space for

some of Hemsleys’ domestic servants—most likely all enslaved Africans—to live and room, and also for equipment for their assigned tasks. In a manner more akin to the townhouses of Philadelphia than the plantations on the Western Shore, Col. William Hemsley built a brick hyphen to connect a back building and kitchen, also in brick, that trailed off the rear of his house….The spaces removed the servant living quarters from the main body of the house, which had until then appeared to have included room for them in the garret.

In the report, full version available here, Graham also expounds upon Hemsley’s life and upon the historical significance of the era to which the house will be restored.

He reflects that William’s marriage to Sarah Williamson (1746-1794) in 1767 was the likely “impetus for a stylistic makeover of the house that fine-tuned the interiors to the degree of elaboration befitting a late colonial seat.” They remodeled “virtually all surfaces on the two main floors.”

They narrowed the front windows to better proportion them for sash. The “windows were also cut into the two gables, which helped brighten an interior that had grown dimmer by the addition of rear chambers constructed for William’s father.” They also had a passage added into the old hall. “That was the final organizational piece that made the house work like a conventional Georgian-plan arrangement,” Graham explains. Another addition they completed was a chimneypiece in the dining room, as part of their project to convert it into the primary entertaining room. The frieze portrays a hunt scene which comes from Thomas Johnson’s volume One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (London, 1761). Graham thinks of it as “one of the finest pieces of rococo carving found in the South.”

However substantial the additions, William and Sarah maintained many of the most significant architectural features from earlier eras. Among them we find the original staircase. As Graham points out, “the balustrade survives as one (if not the) earliest stair in the South and certainly is one of the most impressive of the early eighteenth century.”

Choosing the year 1784 allows us to restore this stair, the chimneypiece and the service wing, therefore prioritizing the moment in history when Cloverfields was a power house, which coincides with a defining moment of Maryland history.

* * *

There is yet another reason behind our choice. During the second half of the eighteenth century there were several outbuildings in the yard. If and when reconstructed, they would provide important context for the main house. In addition, there are a few historic houses located a short distance away from Cloverfields that date from the Revolutionary era or earlier. If restored, Cloverfields and these other buildings would form a consistent ensemble.

The fact that the team feels prepared to recommend the historic period to which the house should be restored does not imply that our research and documentation efforts are complete. The team will continue to conduct research on the history of the house, the gardens and its inhabitants.

Determining the year to which the house will be restored, however, represents a significant step. It will allow me (and my team) to start producing the drawings and blueprints necessary for the restoration to accurately reflect the house as it stood in 1784.

By: Devin Kimmel, AIA, ASLA, for the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation