In This Issue: Completion of the Ice House, and Imagining a Summer Meal with the Hemsleys. Also, Restoration Team Members Win Four Awards.

/Rebuilding the Ice House and Wellhead

The March 21, 2019 newsletter announced Applied Archaeology and History Associates’ discovery of a rare wood-lined ice house. Earlier this year, Lynbrook of Annapolis finished reconstructing it and the adjacent wellhead based on archaeological evidence and architectural research.

Figure 1: The recently completed ice house and wellhead were conveneintly situated near the kitchen. Source: Cloverfields Preservation Foundation.

Figure 2: The reconstructed ice house and adjacent wellhead are part of CPF’s effort to restore the work yard area. This busy space played a central role in supporting the day-to-day operations of the main house and is critical to understanding the experiences of those who labored here. Source: Cloverfields Preservation Foundation.

Background

In 2018, a geophysical survey of the Cloverfields side yard revealed an area of ground disturbance about 35 ft. east of the house. Dr. Tim Horsley conducted the survey and interpreted the subsurface anomaly as buried walls enclosing a roughly 13 ft. x 9 ft. area. Prior to excavation, archaeologists tentatively identified it as the site of the former milk house, which was among the outbuildings listed in the 1798 Federal Direct Tax assessment for Cloverfields.

By the time the field crew reached the bottom of the feature, it was obvious they had found the remains of an eighteenth-century ice house. The excavation revealed the remains of a low brick foundation supporting a wooden superstructure that had capped a sloping pit. Archaeologists also found the remains of pine planks that had once lined the pit’s walls and floor. Artifacts, including the presence of wrought nails and tin-glazed earthenware, dated the structure to the eighteenth century and the ownership of Col. William Hemsley (1736-1812). The wood lining proved particularly interesting as most known ice houses had subterranean walls of brick or stone. Wood linings were uncommon, but known examples include one belonging to George Washington at Mt. Vernon.

In case you missed it, in this 2019 video, Jason Tyler, with Applied Archaeology and History Associates, discusses the discovery of the ice house and compares it with one built for George Washington at Mount Vernon. Video credit: StratDV Video Production.

Mistake or Mistaken Identity?

The ice house discovery was somewhat of a surprise as the 1798 tax record for Cloverfields lists numerous service structures but does not mention an ice house. Presumably, the enumerator overlooked it or failed to look closely and marked the structure down as a milk house, a far more common type of cold storage facility. One expects an estate like Cloverfields to have both.

The enumerator’s possible misidentification can be forgiven as ice houses were a comparatively rare feature on the early-Federal landscape. In the Chesapeake they are almost exclusively associated with high-status properties. A properly functioning ice house required skilled construction and considerable labor to fill.

Figure 3: Cloverfields Ice house interior. Subterranean pits lined with brick, stone or, in this case, Wood, are the distinguishing feature of an ice house. Source: Cloverfields Preservation Foundation.

Stocking an ice house was a straightforward but cold, arduous, and potentially dangerous task. Workers cut blocks of ice from frozen rivers and ponds with saws and axes and then hauled it away by wagon. Back at the ice house, the crew lowered their frigid harvest into the pit, packed it down, and covered it with an insulating material, such as straw. Snow was gathered when ice wasn’t available, though it melted far more quickly.

Mutual Connections

Robert Morris, known as “The Financier of the American Revolution,” was a friend and war-time colleague of both Col. Hemsley and George Washington. Washington and Morris exchanged letters about ice house design and commiserated over the difficulty of preserving snow. In 1784, Morris, living in Philadelphia, wrote to Washington, “I tried snow one year and lost it in June.” He later observed “ice keeps until October or November.” [1]

One is tempted to make a connection between Hemsley and Washington, both of whom had rare wood-lined ice houses, and Morris, whose opinion on ice house design was valued and whom they both knew well. Unfortunately, while Washinton or Morris’s influence on the Hemsley ice house seems possible, it is so far not provable.

The Hemsleys benefited from their proximity to fresh water in procuring ice. Although Cloverfields stands between two branches of the Wye River, the water is brackish. Nearby Tuckahoe Creek, which feeds the mill pond at Wye Mill (owned wholly or in part by William Hemsley or his descendants from 1777- 1845), provided a source of fresh water ice .

In addition to being a refreshing luxury in the summer heat, ice was important for food preservation. Thomas Jefferson points this out in an 1809 letter to his overseer where he writes, “It would be a real calamity should we not have ice… as it would require double the quantity of fresh meat etc. in summer had we not ice to keep it.”[2]

How long into warm weather ice lasted depended on a number of variables. Naturally, the larger and deeper the pit, the longer ice lasted. The Cloverfields’ ice pit is relatively shallow, measuring approximately seven feet deep. There is no record of how long ice typically survived inside, nor is it clear from archaeology when the building ceased to be used for its intended purpose.

Around the mid-nineteenth century, the lining had deteriorated, and the pit transitioned into a household trash dump. By then, the ice house was obsolete. Commercially harvested ice from New England and the upper Midwest went by train and steamship to most parts of the country to fill the kitchen ice boxes of middle-class consumers. The 1884 estate inventory of Marcia Watts Forman, the widow of William Hemsley Forman (great-grandson of Col. Hemsley and wife Henrietta Maria Earle), lists a “refrigerator” (ice box) in the hall. The modest $1.00 value is the same as that given to the adjacent hat rack and slightly less than the $1.25 valuation of two nearby chairs. Mrs. Forman’s inexpensive refrigerator successfully illustrates the near-complete democratization of ice over the course of one century.

Figure 4: Exceprt from Marcia Watts Forman’s estate inventory. The refrigerator (Ice Box) in the hall is valued at only $1.00. Source: Queen Anne County Inventories, Book WET1, Page 429.

[1] George Washington to Robert Morris, June 2, 1784. The George Washington Papers, Series 2, and Robert Morris to George Washington, June 15, 1784. The George Washington Papers, Series 4. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0315-0001

[2] Thomas Jefferson to Edmund Bacon, January 3, 1809. Thomas Jefferson Papers, Huntington Library. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-9464

Chilled to Perfection: The Ice House and Dining Room in Conversation

By Rachel Lovett, Furnishings Consultant

Introduction

Imagine a hot July afternoon in 1784 inside the elegant dining room at Cloverfields. No one is yet present; however, the table is laid out for a mid-afternoon meal for six guests, with green feather edge English creamware.[1] The room’s temperature hovers just below a sweltering 85 degrees Fahrenheit while the humidity feels as if the nearby Wye River is pooling into the room. Wafting through the open window is the scent of freshly baked bread from the nearby kitchen, signaling that the meal will soon be ready.

Figure 1: Example of 18th century green feather edge English Creamware. The 1812 inventory lists 92 pieces of this ceramic type.

Luckily for the Hemsley family and their guests, the estate has an ice house, a rare luxury in late 18th-century America, mainly found on southern plantations. Soon Colonel William Hemsley and his wife Sally will lead their party into this space to enjoy cooling libations and custards to break the Maryland heat.

The Hemsleys hosted many of Maryland’s elite gentry in the late 18th century, including the family of famed portrait artist John Hesselius and Edward Lloyd IV of nearby Wye House, known to his friends as “The Magnificent” for his wealth and status.

Designing for Dining

The discovery of a rare wooden lined ice house at Cloverfields, uncovered in 2019, is a key component in understanding on-site hospitality in 1784, CPF’s year of interpretation. The availability of ice meant the family could enjoy cold libations and specialty desserts, unobtainable to those without access to that rare summer commodity. The dining room furniture plan has been selected with this in mind.

A careful examination of the 1812 inventory of Colonel William Hemsley (1737-1812) revealed items likely used by the family for chilled desserts and beverages in 1784. Side tables came into wide use in the years after the American Revolution and were commonly found along the perimeter of parlors and dining rooms in affluent homes. One of the most notable pieces listed in the 1812 inventory is a marble slab side table, a piece that fused fashion with function. Unlike a wood top, such as mahogany or walnut, marble is heat resistant and impervious to liquids, meaning hot dishes, cold desserts, and chilled iced beverages could safely be placed on it without concern for condensation or heat marks.

While marble slabs had been used in Europe for centuries, their use in America was just coming into vogue in the 18th century, and few early examples survive. Eighteenth-century American cabinetmakers crafted the table’s wood frame to accommodate marble sourced from continental Europe. Notable contemporary pieces are found in historic houses and museums, including George Washington’s Mount Vernon and the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis, Maryland. Colonel William Hemsley’s brother-in-law Colonel Tench Tilghman (1744-1786) of Talbot County, Maryland, owned a fine Chippendale-style marble top pier table with a mahogany frame made in Philadelphia c. 1765.

Figure 2. Marble Slab Table at George Washington's Mount Vernon. Purchase, 1950 Conservation courtesy of The Founders, Washington Committee Endowment Fund. Object Number W-1546

Another item on the estate inventory useful for serving chilled items was a glass dessert pyramid with 47 components. This piece likely had several oval glass stands and smaller cups used for custards, fruits, and ice cream. These smaller cups were placed on top of the oval stands.

Dessert pyramids were once a cornerstone of grand 18th-century dining in the Chesapeake. Due to their fragility and the large number of small portable components, intact extant examples are now even rarer than marble slab tables. Functionally designed to present enticing sweets, the equally important goal of these pieces was an elegant display of symmetry for the table. Contemporary recipe manuals such as Hannah Glasses 1760 The Complete Confectioner suggested stacking salvers with the largest at the base, so it was essentially the shape of a pyramid.

The Process

Lynbrook of Annapolis reconstructed the ice house and wellhead based on designs by architectural historian Willie Graham, who has served as CPF’s restoration and preservation consultant since the start of the project. Graham based his plans on archaeological evidence and his extensive knowledge of other examples from the period.

Together, Lynbrook and Graham created the appearance of a historic construction by using traditional materials and paying strict attention to details. Hand-forged nails, replica sash-saw marks, custom-made bricks and, in the ice house, rafter pairs numbered with Roman numerals are among the elements that allow the structures to hold up to scrutiny. For durability, modern materials, such as CMU blocks and pressure-treated lumber, were used in areas outside of the public eye.

Figure 5: Lynbrook of Annapolis reconstructed the Ice House using Willie Graham’s design. Graham based the construction drawings on archaeological evidence and comparisons with similar structures from the period. Visible elements look like period construction, while modern methods invisibly address practical considerations, such as drainage and discouraging snakes.

Image 6: This photograph from 1935 shows the former ice house at Marmion, near Comorn, in King George County, Virginia. It features the same type of A-Frame superstructure and low foundation as that interpreted at Cloverfields. Source: Historic American Building Survey, Library of Congress, HABS VA, 50-COMO. V,2-26.

Figure 7: This photograph from about 1930 shows a young Mary Callahan (later Pippin) in front of the well and ice house location. By this time, a pump had replaced the wellhead and only debris marked the location of the ice house. For reference for those familiar with the property, The white building to her left is the location of the current visitor center and office. Source: Mary Callahan Pippin Collection.

Kimmel Studio Architects Receives Two Awards for Cloverfields Projects

CPF congratulates Devin Kimmel, AIA, ASLA and the talented team at Kimmel Studio Architects for winning two awards for Cloverfields projects! In May, the Institute of Classical Art and Architecture presented the firm with the prestigious John Russell Pope Award in Historic Preservation. In their announcement, ICAA highlighted KSA’s innovative approach to the Cloverfields restoration.

As lead architect, Devin developed the master plan and design to restore the house and gardens. The approach carefully balanced faithfulness to the original materials and character of the 1705 home and its formal gardens while integrating contemporary construction methods and sustainability measures. About the award, Kimmel said, “The project was a beautiful interplay of colonial and contemporary design and methods, giving us a rich sense of timelessness."

Figure 1: Devin Kimmel, lead architect and managing principal with Kimmel Studio Architects, receiving the 2023 Maryland Association of Landscape Architects Merit Award.

Kimmel Studio Architects also received the 2023 Maryland Association of Landscape Architects Merit Award for General Design. This prize recognized KSA’s concept for restoring Cloverfields’ terraced gardens. Kimmel and the team based their interpretation of the gardens’ 1784 appearance (CPF’s period of interpretation) on evidence from ground-penetrating radar, archaeological discoveries, and period writings. The Merit Award recognizes superior professional accomplishment. Congratulations!

Figure 2: Thie Sun rises over Cloverfields and Kimmel Studio Architects’ design-winning work.

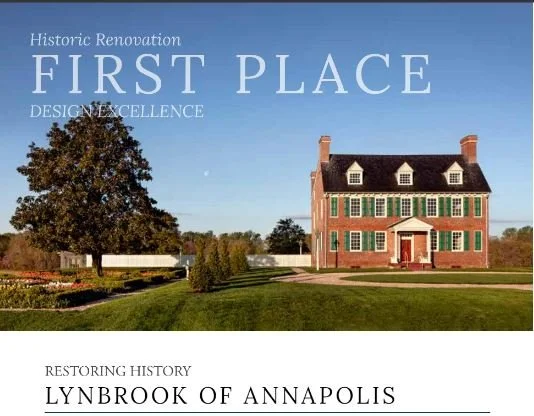

Lynbrook of Annapolis Receives Two Annapolis Home Builder and Fine Design Awards

The accolades keep coming in for CPF’s team of experts. The biennial Annapolis Home Builder and Fine Design Awards recognize high achievement in architecture, custom building, interior, and landscape design. Judges are distinguished professionals in their respective fields. The January 2023 edition of Annapolis Home Magazine announced the most recent winners. Lynbrook of Annapolis was honored with two awards, including First Place for Historic Renovation Design Excellence for Cloverfields, and First Place for Total Home Project by a Team of Professionals (Custom Building) for a contemporary design. Well Done!

Figure 1: Congratulations to Lynbrook of Annapolis for their ttwo recent awards. Source: Annapolis Home Magazine, Vol. 14, no. 1 2023.

Chilled to Perfection (Continued)

Figure 3: Example of a Dessert Pyramid. Source: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The first recorded serving of ice cream in America was at a dinner party given by Maryland Governor Thomas Bladen in Annapolis in 1744. Ice cream steadily gained popularity in the mid-18th century, although many of the flavors would be somewhat foreign to the 21st-century palate, such as savory ones like Avocado and Artichoke. However, sweet flavors like Citrus, Strawberry, and Mint, all popular in the 18th century, have stood the test of time.

In 1784 George Washington ordered a “cream machine for ice, and rebuilt his ice house. In 1790 Washington spent the modern-day equivalent of $6,500 on ice cream alone. Thomas Jefferson left for France in 1784 and returned with an ice cream recipe that helped popularize the dessert amongst the American public. Colonel William Hemsley likely had ice cream during this time in Philadelphia during the years of the American Revolution. Ice cream was popular in Philadelphia, as it was served at City Tavern, which hosted many of the city’s Revolutionary celebrations

Ice cream at Cloverfields was likely eaten with ivory-handled dessert forks. In a November 15, 1763 letter from Colonel William Hemsley to his London agents James and Richard Christie, he ordered a dozen dessert knives and forks in a mahogany case. These pieces also appear in the 1812 inventory, so they were still in use in 1784. Other items used during this period include two meat tins “for the ice house.” The ice house was likely the same building referred to in the 1798 Federal Direct Tax as a milk house. Eighteenth-century milk houses, also known as dairies, did not house milk cows. Instead, they acted as cold storage for milk, butter, cheese, and other perishables.

Figure 4: Ivory Handled Cultlery. Source: Artemis Gallery.

Behind the Scenes

The realm of the ice house/dairy at Cloverfields during this period was overseen by an enslaved woman and estate favorite Nannie Faithful, who, along with her husband Charles, appeared in the 1812 list of enslaved workers. Nannie was then age 70, and Charles was age 82. Given their ages, the couple was likely at Cloverfields in 1784.

Sources suggest the couple played an integral role in daily life at Cloverfields. Hemsley descendent Frederic Emory noted in an 1886 account that according to Colonel William Hemsley’s granddaughter Henrietta Troup, “Charles was chief lieutenant at Cloverfields… who rode around on horseback to the different farms to obtain supplies of butter, eggs, etc.” and Nannie was “held in high esteem by the family, no one acquainted with the customs of the household, ever thought of visiting Cloverfields without paying respects to the able dame, who generally received visitors at the dairy, her special domain always looking fresh and neat in her white cap and kerchief.”[2] While the roles of the Faithfuls are defined in the historical record, less is known about the kitchen staff who prepared the meals and served them in the dining room. In 1784 the well-appointed dining room at Cloverfields ran like a Michelin-star restaurant. An enslaved cook, equivalent to a modern-day chef, was one of the most skilled people on the estate. They orchestrated elaborate midday meals assisted by several assistants who acted as sous chefs in the kitchen, which in 1784 was a new addition to the back of the mansion.

The grand spectacle of food required additional skilled servants for presentation and serving. They, as well as the hosts and the guests, understood the etiquette that elevated dinner from a simple meal to an ostentatious event. A 41-year-old woman named Rachel and a 43-year-old woman named Molly are listed on the 1812 inventory as house servants. Rachel and Molly could have easily been in the house in 1784 at age 13 and 15, respectively, and assisting in the servants’ hall or dining room during meal services.

For those with economic resources to entertain in a grand fashion, like the Hemsleys, dinner was generally eaten in the mid-afternoon and was the day’s main meal. It would consist of multiple courses, with the first containing soup and meats and the second and even third combining savory dishes like roasts and cooked vegetables with sweets like pies and tarts.

Dinner would end with a dessert course, with the tablecloth removed and an impressive centerpiece full of fruit and sweets laid before the diners with devices like a dessert pyramid. Dining in the late 18th and early 19th century was an involved process that could take up to several hours. Conversation was important as it was expected that you would converse with your host and guests at length. Possessing a charming and witty disposition went a long way to gaining the respect and admiration of your fellow guests. Given the distance between houses, guests often stayed the night, as travel was especially difficult in the dark. After dinner, guests enjoyed games, dancing, and music in the second-floor drawing room at Cloverfields.

In the coming months, Cloverfields Preservation Foundation will be working on acquiring furnishings, textiles, and floor coverings for the mansion. Each room at Cloverfields has been meticulously researched to create vignettes that pay tribute to the stories and people who once called this place home. The goal for the furniture plans at Cloverfields is to give an air of authenticity to each space so one can imagine daily life in 1784, by acquiring items that actually existed in the home, like a marble slab table and a dessert pyramid for the dining room.

Figure 5: Hammond-Harwood House Dining Room Table. Source: Hammond-Harwood House.

[1] The 1812 Inventory identifies 92 “Green Edge” mid-18th century English-made creamware plates and two green edge soup tureens. Appropriate examples have now been acquired as a Foundation purchase from the Talbot County Historical Society in 2022. Cloverfields Preservation Foundation, No. 2022.70.1-13.

[2] 1886 Frederic Emory Unpublished Manuscript. The Hemsleys of Maryland. H. Furlong Baldwin Library, Maryland Center for History and Culture.