In This Issue: Discovering William Hemsley, Jr. (1766-1825) in Art and Life, CPF Acquires the Hemsley-Forman Desk and Bookcase, and Summer in Review

/Miniature Portrait believed to show William Hemsley, Jr. (1766-1825) as painted in 1802 by Robert Field (1769-1819). Image Courtesy of Thomas Edgar.

Discovering William Hemsley, Jr. (1766-1825) in Art and Life

CPF recently received an interesting and welcome email from Tom Edgar, a Hemsley descendant through the Emory line. Mr. Edgar owns a framed miniature portrait that, according to family tradition, depicts a member of the Hemsley family. Interested in learning more about the piece, Mr. Edgar reached out to other relations and eventually was put in contact with us. Evidence, to be detailed in a future newsletter, led CPF historian, Sherri Marsh Johns, and decorative arts consultant, Rachel Lovett, to conclude that the elegantly dressed gentleman shown in the portrait is likely William Hemsley, Jr. (1766-1825), as painted by English-born artist Robert Field (1769-1819) in 1802.

William Hemsley, Jr. was the eldest son of Col. William Hemsley (1766-1812) and the former Henrietta Maria Earle (1730-1767). Known as Will to family and friends, he was the last of the Hemsley name to reside at Cloverfields. If correct about the sitter's identity and the portrait’s date, Will is thirty-six and shown as he appeared around the time of his marriage to his nineteen-year-old cousin Maria Lloyd (1784-1803).

The image shows a mature man, poised and confident, with wide blue eyes and a mouth conveying just a hint of a smile. Hemsley's unhappy biography is at odds with the sitter’s sanguine expression. Born with every advantage the age could offer, mental illness and plain misfortune thwarted his personal happiness and professional aspirations. Family letters reveal a stalwart man who courageously pushed back against sickness and tragedy by seeking solace in religion and family.

Will studied law and started his career as a country lawyer, working for a time in Hagerstown, and as a gentleman farmer, managing his father's nearby Hopton and Wye Mill estates.

1797 marked an important turning point in Will's life. Through his father's connections, he received a prestigious diplomatic assignment to serve in London as secretary to Rufus King, the newly appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain.* His Tilghman relations used his impending departure as a welcomed opportunity to return their widowed in-law Harriett Milbanke Tilghman and her young children to London.

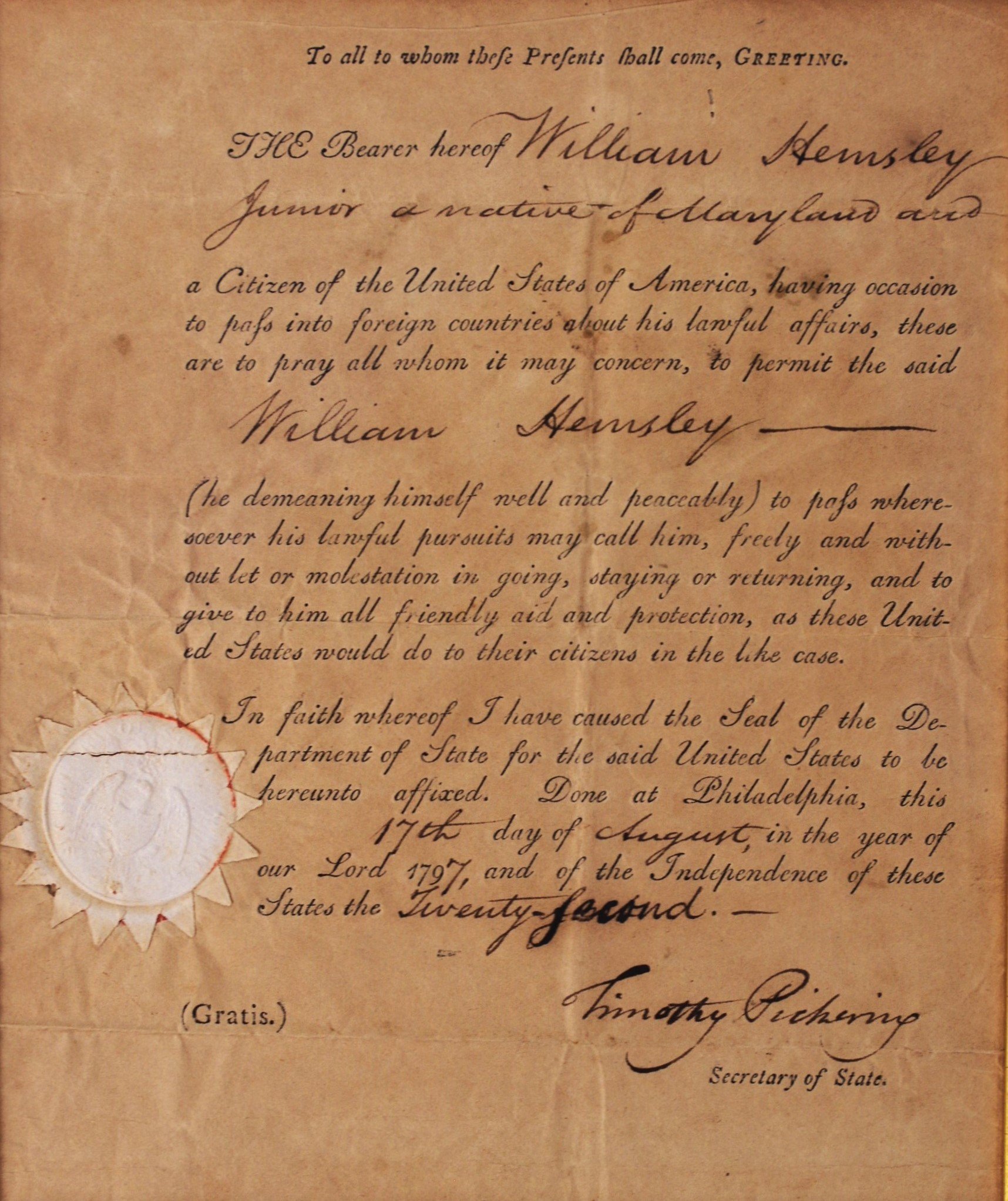

William Hemsley, Jr.’s 1797 passport. Source: Cloverfields Preservation Foundation Collection.

Harriett's story reads like the plot of a Jane Austen novel. Will's many cousins included Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman (1744-1786), who served as aide-de-camp to Gen. George Washington during the American Revolution. Tench's brother Philemon Tilghman (1760-1797) also fought in the Revolution but on the other side, having run off at age sixteen to join the Royal Navy. Both men were Col. William Hemsley's first cousins and brothers of his third wife, Anna Maria "Nancy" Hemsley (1750-1817).

Harrriett Milbanke Tilghman (1765-1835). Source: Royal Descent https://royaldescent.blogspot.com/2016/05/ruvigny-addition-descendants-of-harriet.html

Philemon, by most accounts a rake lacking in money but not audacity, had eloped with Harriett Milbanke (1765-1835), the beautiful daughter of his commanding officer, Admiral Mark Milbanke. The furious Milbanke disowned Harriett, and the shunned couple sailed to Maryland and moved in with Philemon's father, James Tilghman (1716-1793), at Golden Square.

Philemon died in January 1797, having spent the inheritance received from both his father and a late brother. To relieve themselves of the prospect of supporting a young widow with five children, Philemon's relations, including Col. William Hemsley, raised money for Harriett to accompany Will on his voyage to London in hopes she would reconcile with her family.

The Milbanke family reunion succeeded, but Will's diplomatic career failed. Within six months he left his position with Rufus King and returned to Maryland. According to the 1886 manuscript, The Hemsleys of Maryland: A Genealogical Sketch by Frederick Emory, Hemsley was shipwrecked on the return voyage. Emory writes that the near-death experience affected a profound religious conversion, after which “he lived the life of a sincerely pious man."

The Hemsleys attended services at St. Paul’s Parish, better knon as Old Wye Church, begining with its dedication in 1721. During periods without ordained clergy, the vestry accepted will hemsley’s offer to serve as lay reader. Photo by Willie Graham.

Unlike some bargains made with the Almighty during times of great crisis, Will's new-found faith remained steadfast for the remainder of his life. Records of Old Wye Church record Hemsley as a long-serving lay reader and one of the "faithful fourteen" (most of whom were Hemsleys or close relations) who kept the church going during the difficult years of the early nineteenth century. He seriously considered entering the clergy and, through the careful study of Scripture, concluded that the enslaving of humans was incompatible with Christian principles.

Hemsley wrote a series of letters to Bishop James Kemp regarding slavery, including one in which he posed a series of queries about its morality and Christian obligation.

In “Queries,” WilLiam Hemsley, Jr. asks Bishop Kemp his thoughts on the morality of perpetual slavery, why the apostles did not call for emancipation, and the responsibility of an owner who believes holding humans in perpetual bondage to be antithetical to Christian living.

While wrestling with these matters, Will prepared for marriage to his cousin Maria Lloyd (1784-1803). Their short, unhappy union appears to have been a marriage of convenience between two people in uncertain circumstances. At nineteen, Maria was half the age of her bridegroom. From her widowed father, former U.S. Senator and future General, James Lloyd (1756-1830), Maria received a distinguished name but little or no dowry.

Lloyd’s steep debts and heavily mortgaged property motivated him to write to President George Washington for assistance. Reminding Washington of his service to the nation, Lloyd requested an appointment and, confessing in considerable understatement, that he could not make "comfortable provision for a large and encreasing [sic] family. Lloyd did not receive the requested appointment, went on to lose the family estate, Farley (or Fairlee), and after losing his wife and marrying off two of his three daughters, spent the last decade or so of his life living with various relatives. He is buried at Cloverfields with all three daughters.

Will and Maria married early in 1802. In August, Col. Hemsley wrote his cousin and Maria's uncle, William Tilghman, with news that Will had experienced another breakdown and had been away from home for two weeks, "which has made him even more miserable." He wrote, "Poor Maria's fate is a melancholy one and it has destroyed the peace of both families." How the situation resolved in the short term remains unknown, but the couple’s troubles ended the following May with Maria’s death.

The last ten years of Will Hemsley's life are not well documented. In 1812, he inherited Cloverfields. The young nation was again at war and entering a protracted economic crisis that ruined many Hemsley friends and relations. Intervention by nephew Ezekiel M. Forman (1790-1823) kept Will from insolvency and prevented the sale of Cloverfields, as well as the Wye Mill inherited by Will’s younger brother Alexander.

Ezekiel and his bride Henrietta Earle Forman took up residence at Cloverfields with Will and his older sister Charlotte. Hemsley wrote his will in 1821 and named Forman as the principal heir to both his real and personal estate, excepting his enslaved people who are discussed later. Forman predeceased his uncle by two years. In his 1822 will, Ezekiel refers to his Hemsley as "a father and a friend." He "fervently…solemnly and affectionately" asked Henrietta to remain at Cloverfields under Hemsley's “protection” and strongly discouraged her from remarrying.

William Hemsley, Esq. (no longer styling himself "Junior" since his father's death) died in 1825. He had added a codicil to his will leaving Cloverfields and most of his personal estate to Ezekiel and Henrietta’s sons. His ledger stone in the Cloverfields cemetery reads in part, "This stone is dedicated by the widow and fatherless children of his nephew who found a shelter in his love and protection. Reader be moved." At William's death, those fatherless children, William H. and Ezekiel T. M. Forman, then ages five and two, became the juvenile owners of Cloverfields.

Hemsley’s will provided for the gradual emancipation of his enslaved people (except those above age forty-five who were prohibited freedom by law). He ordered men to be granted their liberty at twenty-six and women at twenty-three. Persons already of the specified age were obligated to serve two more years, except for Mordecai Moore, who was to remain bound for one more year. Hemsley gave to Ezekiel Forman’s "care and attention" those persons awaiting their freedom or too old to be legally granted it,

More than fifteen years before his death, Hemsley asked Bishop James Kemp the proper course of action for a slave-holder who found slavery contrary to Christian doctrine. The Bishop provided no useful guidance. His response is roughly summed up as "there is no good choice." There is no record Hemsley personally owned enslaved people before inheriting Cloverfields. The estates he managed and those who labored there were his father's. Still, given his convictions, what circumstances prevented him from liberating those he inherited sooner?

On the other hand, the 1808 ban on the importation of slaves into the United States drove up the value of enslaved workers so much so that it led to the organized kidnapping of free blacks. Col. Hemsley remarked on the high prices paid by buyers from the Deep South. He wrote critically of those who sold enslaved people to the deep-pocketed southern buyers, citing the brutality of conditions there and the cruelty of breaking up families. Despite his near insolvency, Will Hemsley did not use his valuable human capital as a means to free himself from debt.

The historical record is fragmentary and incomplete. As with the Field miniature, surviving documents reveal Will Hemsley, Jr.'s life at discreet points in time. Much remains unknown. Previous newsletters have highlighted the Hemsley family’s wealth and political power, and how they carefully projected this image against the beautiful backdrop of Cloverfields. Will Hemsley's sad story offers a valuable counterpoint by showing that Cloverfields’ façade also beautifully concealed the same family’s weakness, pain, and loss.

* A lower rank than ambassador. As a republic, the United States did not exchange ambassadors with Great Britain until a policy change in 1893.

Fall Arrives at Cloverfields

Seemingly oblivious to the calendar, Cloverfields’ summer flowers remain in bloom, but the neighbor’s harvested cornfields rebut our dissembling flora, insisting fall has indeed arrived.

When the Hemsleys lived at Cloverfields, summer was the “sickly season.” Happily, those of us working at Cloverfields stayed well and enjoyed hosting visitors from across the country and around the county, including more than a dozen descendants of the Hemsleys of Cloverfields.

Dr. Hugh Hemsley and family displays the bible of Philemon Hemsley. Photo by Sherri Marsh Johns.

Dr. Hugh and Pam Hemsley of Chesterfield, Virginia, toured the house and grounds with their daughter and two grandsons and brought the family Bible. Philemon Hemsley (ca 1777-1808) purchased the Bible in 1806, the year after marrying Elizabeth Lloyd (1784-1808). Elizabeth’s twin sister married Will Hemsley, Jr., whose life is discussed in the opposite article.

The Bible’s pages record nearly two hundred years of births, marriages, and deaths of this cadet branch of the Hemsley family, up to and including Hugh’s birth. CPF thanks them for bringing this important piece of family history and allowing us to copy the genealogy section.

Hemsley-Emory descendants visit their ancestors and tour the gardens. Photo by Olivia Wood.

A few weeks later CPF received Ms. Olivia Wood and cousins visiting from as far away as upstate New York and California. All are Hemsley descendants through Anna Maria Hemsley (1787-1864), the daughter of Col. William Hemsley (1736-1812) and his second wife, Sally Williamson (1749-1771). After her 1805 marriage to Thomas Emory, Anna Maria moved to Poplar Grove, near Centreville, Maryland. Ms. Wood and husband Eric now own Poplar Grove and have started restoring the family’s eighteenth-century home. Last year Ms. Wood opened her home to visitors from CPF, so we welcomed the opportunity to return the hospitality.

Other visitors included the president of Chesapeake College, the Annapolis Chapter of The National Society of Colonial Dames of America, Friends of Wye Mill, and Wye Mills Homemakers Club. As the latter group began to leave, four young environmental scientists who were taking soil samples from the neighboring farm came over and asked about the property and for permission to take selfies in the garden. All lovers of history, the group thoroughly enjoyed receiving an impromptu tour of the house and grounds.

Annapolis Chapter of the Colonial Dames-Susan Snyder, Fran Harwood, Bobby Pittman, Madeleins Hughes, Joan Finerty and Amy Reese. Photo by Sherri Marsh Johns.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered: The Desk & Bookcase at Cloverfields

By Rachel Lovett, Furniture Consultant

This past spring a rare opportunity presented itself for the CPF to acquire a ca. 1770 desk and bookcase that has a compelling connection to Cloverfields. The piece was owned continuously by one Maryland family, direct descendants of Colonel William Hemsley (1736-1812) through his eldest child, Mary "Polly" Forman. In order to fully appreciate the significance of this piece within the late-eighteenth-century household, it is essential to analyze its function, form, and provenance.

Desks and bookcases were typically located on the first floor in the parlor for visitors to see in eighteenth-century Maryland. The pieces have been associated with masculinity, and many eighteenth-century male portraits portray the subject seated while reading or writing at a desk. A desk and bookcase conveyed the wealth and intellect of the owner to the viewer; essentially, they were a status symbol.

CPF recently acquired this ca. 1770 walnut desk and bookcase from a Hemsley/ Forman descendant. This may be the walnut desk and bookcase listed in col. William Hemsley’s 1813 estate inventory.

A two-part desk and bookcase is listed in the parlor in Col. Hemsley's 1813 inventory. Given the age of the piece (ca. 1770) and the connection to the Forman family who inherited Cloverfields, it is certainly plausible this exact piece was at Cloverfields. The piece's position in the parlor rather than a private study suggests that multiple family members or visitors may have used it.

In the eighteenth century, letters were often read aloud at family and public gatherings, underscoring the need for discretion in communication. In 1784, Colonel William Hemsley had a private study that served as a sanctuary for confidential matters and correspondence, such as the exchanges related to the unsuccessful courtship of his relative, nineteen-year-old Polly Tilghman, by their neighbor, forty-one-year-old twice-widowed Governor William Paca. Likewise, a July 1793 letter from Hemsley to his friend Edward Lloyd IV was also written in private when he assured Lloyd that his daughter Rebecca's unwanted potential suitor, Joseph Hopper Nicholson, would not be at Cloverfields upon their next visit. Lloyd's objection notwithstanding, Nicholson married Rebecca in October of that year.

This desk and bookcase might have also played a role in the education of Hemsley's children, where they learned the art of penmanship. Children in the period learned to read after age four, however, they did not learn how to write until at least age nine or older. Writing was challenging as it was done with a quill pen, generally made of a goose feather, and the ink was messy and easy to smudge. While literacy rates were high in late-eighteenth-century America, writing was a skill predominantly possessed by men engaged in business and wealthy women responsible for household management. Once letters were written, they were closed with sealing wax, often stamped with a coat of arms or another sign indicative of the sender. The seal held the pages together to prevent the letter from being read until it was in the hands of the intended reader.

A wax seal with the Hemsley family crest. Image courtesy of the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation.

Previous family historians identified the animal at the top of the shield as a goat, but in a December 15, 1809 letter to William Tilghman, Col. Hemsley describes his crest as an antelope’s head. The shield, with three bars and a lion statant, is the Hemsley coat of arms listed in Burke’s peerage.

This particular desk and bookcase was constructed about 1770 and exhibits characteristics of Mid-Atlantic origin. The piece contains native woods found in Maryland furniture construction during the second half of the eighteenth century. The primary wood is walnut, which was common in Maryland cabinetmaker shops. Colonel William Hemsley's 1813 inventory reflects a high quantity of walnut furniture. The secondary woods for the backs of drawers and bottoms are yellow pine and tulip poplar, which is also in keeping for a Maryland-made piece. The piece has a broken-arch pediment and an urn-and-flame finial that may be replacements. Notable on the piece is the high quantity of drawers, which would be spaces where valuable papers could be hidden. The prospect door, which is the locked door on the interior of the slant top, is thought to be a replacement along with the ogee bracket feet.

Overall, the piece is in fine stable condition. Generally, country plantation seats would contain simpler furnishings compared to city dwellings. So, while this piece is not as fancy as other examples from Annapolis, Philadelphia, or New York, it is likely more in keeping with what existed at Cloverfields in 1784.

Until this past spring, the desk and bookcase were owned by Laura Eddy, a Hemsley/Forman descendent from Easton, Maryland. Family history states that the desk has provenance in the Forman family for over two hundred years. According to family history, the piece descended through the line of the Forman family, dating all the way back to Col. Joseph Forman and his wife Mary "Polly" Hemsley, the eldest child of Col. William Hemsley. Col. Joseph Forman (1761-1805) and Polly (1760-1795) were married at Cloverfields on Polly's 22 birthday, April 30, 1782.

The marriage produced four children. The couple's third son, Maj. Ezekiel Marsh Forman (1790-1823), was set to inherit Cloverfields upon the death of his childless uncle, William Hemsley Jr. (Colonel William Hemsley's eldest son/Polly's younger brother). However, Ezekiel, who, along with his family, had already taken up residence at Cloverfields, died unexpectedly in 1823, predeceasing his uncle by two years.

Next in line were Ezekiel's very young sons, William H. Forman and Ezekiel T. M. Forman, the great-grandsons of Colonel William Hemsley. When the Formans inherited the property in 1825, they obtained the home's contents, possibly including this desk. William died in 1868 (then having sole ownership of the house). Notably, William’s 1868 estate inventory includes a valuable secretary and bookcase. He left his real and personal estate to his wife Marcia Watts Forman for the duration of her life and upon her death in equal shares to his six children.

Marcia rented out Cloverfields during her children's minority but was again living there at the time of her death in 1884. Her estate inventory makes no mention of a desk, but notably does include a bookcase in “Room No. 1 below stairs.” At $5.00, it is the most valuable piece in the room, exceeding the $3.00 walnut table, $3.00 carpet, and $2.00 chaise lounge.

The next known owner of the desk is Laura Gold Forman Grymes. Born in 1867, she was the only daughter of William and Marcia Forman. Cloverfields continued in the Forman family until 1897, when Laura's eldest brother Frederick Watts Forman and "co-heirs," including Laura, sold Cloverfields to Thomas H. Callahan, Sr. At this time, the estate dispersed, and Laura took possession of the desk and bookcase, assuming she had previously done so. Laura gave the piece to her daughter Marcia Watts Grymes, who gave it to her son Peter Hersloff, the father of the most recent former owner, Laura Eddy, who sold the piece to CPF.

Given the provenance, design, and age of this piece, it was worthy of acquisition for the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation. Now on display (with brasses freshly polished by Estate Manager, Jim Barton), the desk and bookcase has made an excellent vignette in the first-floor parlor to give the space an air of authenticity.